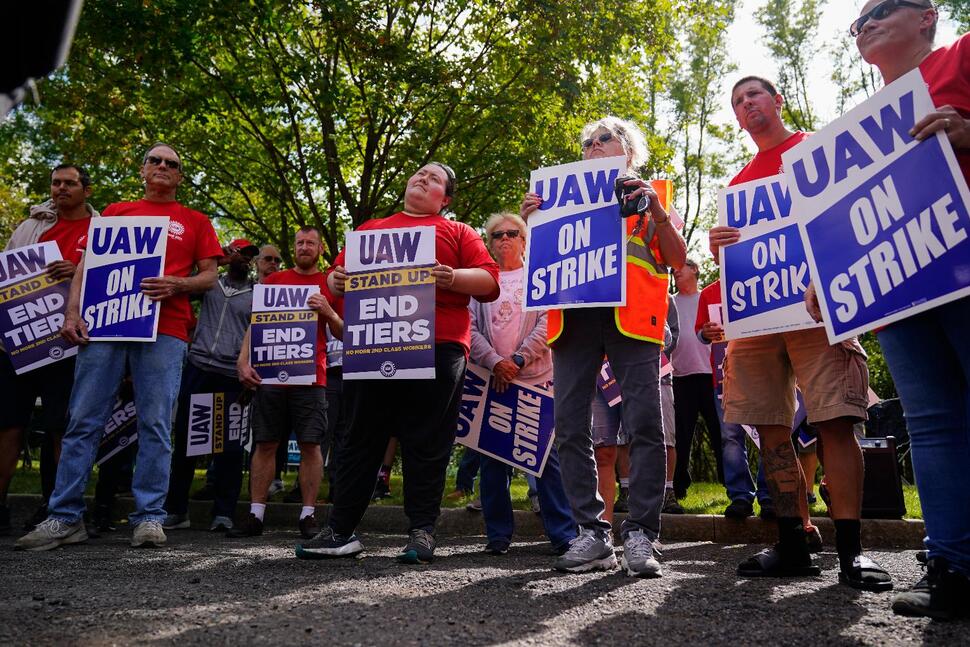

The strike by the United Auto Workers is expanding. The UAW on Friday walked out of dozens of plants located across 20 states, marking the end of the union’s record work stoppages against major automakers after one week.

After the union’s contract with those businesses ended at Midnight on September 14th, the UAW started conducting targeted strikes against General Motors, Stellantis, and Ford. At the time, 13,000 employees left three assembly sites, and union leadership issued a warning that more locations might be affected if contract negotiations didn’t make considerable headway.

Although neither party made any progress during Thursday’s negotiations, the UAW stated on Friday that it will be shutting down 38 more Stellantis and General Motors parts distribution sites. Approximately 13% of the union’s 146,000 members—or another 5,600 workers—have already joined the picket lines.

According to UAW President Shawn Fain, Ford avoided fresh strikes on Friday because the business acceded to some of the union’s requests during talks over the previous week.

The UAW is asking for significant hikes and better benefits, citing the three firms’ recent earnings and increases in CEO pay. Additionally, they want to recover concessions that the workers made in the past.

The Detroit Three contend that they must use their revenues to pay for a pricey switch from gas-powered to electric automobiles, so they cannot afford to comply with the union’s requests. Tensions increased during the past week as businesses fired thousands of employees, claiming that certain firms were lacking in parts as a result of the strike.

Since there is no promise of a resolution anytime soon, the strike might ultimately have a big negative impact on American auto output. What you need to know is listed below.

WHAT WANT THE WORKERS?

The union is requesting 36% increases in general compensation over the course of four years; the top-scale assembly plant employee now makes around $32 per hour. In addition, the UAW has demanded a 32-hour workweek with 40 hours of pay, the restoration of traditional defined-benefit pensions for new hires who currently only receive 401(k)-style retirement plans, the end of different pay tiers for factory jobs, the end of cost-of-living pay raises, among other benefits.

The union’s ability to represent employees at 10 electric car battery plants, the most of which are being developed through joint ventures between automakers and South Korean battery companies, is perhaps of utmost importance to the union. The union demands top UAW wages for certain plants.

Part of the reason for this is because when the industry converts to EVs, people who currently produce parts for internal combustion engines will need a place to work.

Currently, defined-benefit pensions are not offered to UAW employees joined after 2007. Additionally, their health benefits are less plentiful. Years of general pay raises and cost-of-living wage increases were forfeited by the union in order to assist the businesses in cost reduction. Temporary workers start at slightly under $17, despite the fact that top-scale assembly workers make $32.32 per hour. However, profit-sharing payments to full-time employees this year have ranged from $9,716 at Ford to $14,760 at Stellantis.

The demands of the union are, in Fain’s words, “audacious.”

He argues, however, that the wildly successful automakers can afford to raise workers’ wages dramatically in order to make up for what the union forfeited in order to support the businesses through the Great Recession and the 2007-2009 Financial Crisis.

The Detroit Three have been significant moneymakers during the previous ten years. They reported $164 billion in net profits overall, $20 billion of it this year. The CEOs of the three big automakers each receive an annual salary of several million dollars.