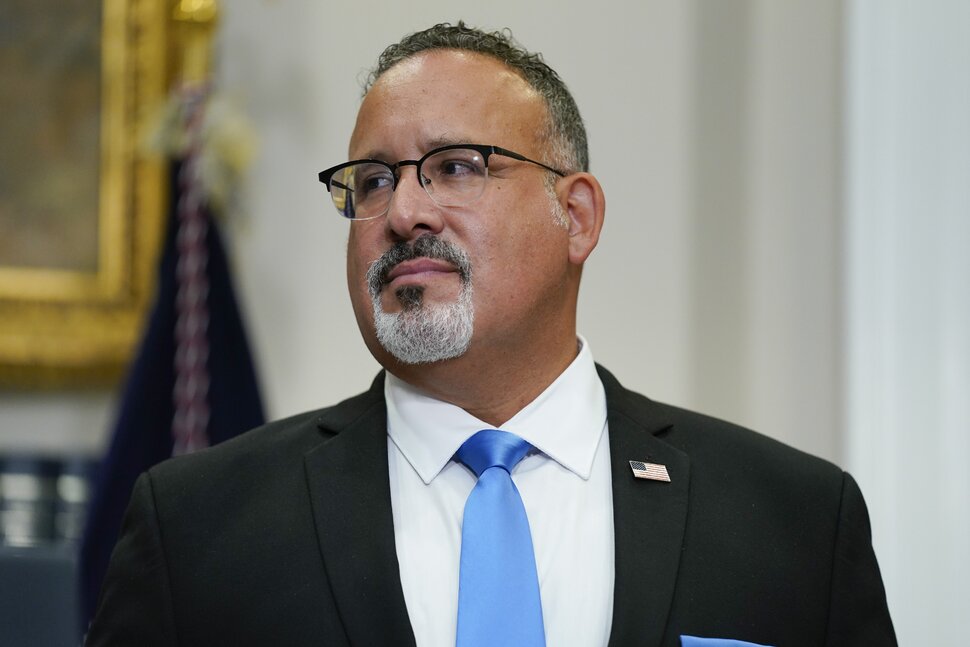

A letter from Education Secretary Miguel Cardona stops short of mandating an end to corporal punishment in 23 states where it is legal, but it outlines the latest research on the effects.

The Biden administration put on notice states where corporal punishment is still legal and used in schools as a form of discipline, warning governors, state education chiefs, superintendents and principals on Friday that paddling, spanking and other physical punishments have no place in K-12 schools.“It’s unacceptable that corporal punishment remains legally permissible in at least 23 states. Our children urgently need their schools to raise the bar for supporting their mental health and wellbeing,” Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said in a statement.

“Despite years of research linking corporal punishment to poorer psychological, behavioral, and academic outcomes, tens of thousands of children and youth are subjected to beating and hitting or other forms of physical harm in school every academic year, with students of color and students with disabilities disproportionately affected,” he said. “Schools should be places where students and educators interact in positive, nurturing ways that foster students’ growth and development, dignity, and sense of belonging – not places that condone violence and instill fear and mistrust.”

The notice, sent Friday in a “Dear Colleague Letter,” stops short of outlining any tangible repercussions for states and districts that continue using corporal punishment, but it offers school leaders the latest research on its negative physical and mental impact on children and includes a promise to help them transition away from such practices.

As it stands, corporal punishment is an allowable form of school discipline in 23 states, with 99% of all instances occurring in 10 states – Mississippi, Texas, Arkansas, Alabama, Oklahoma, Georgia, Tennessee, Missouri, Florida and Louisiana – and 75% of all cases occurring in just four states – Mississippi, Texas, Arkansas, and Alabama, according to analysis of federal data by The Education Trust.

Research shows that corporal punishment is often employed as discipline for a variety of minor or subjective infractions, including dress and hair code violations, talking in class, tardiness, truancy and poor academic performance. And the physical punishments are meted out disproportionately against students of color and students with disabilities. Although Black students account for only 15% of total K-12 student enrollment, they’re on the receiving end of 37.3% of all instances of corporal punishment.

And while instances of corporal punishment significantly declined over the last decade, more than 98,000 students across preschool and K-12 schools received corporal punishment, according to the Education Department’s 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection.

The notice from Cardona comes as a handful of states where corporal punishment is still allowed are considering formally banning the practice during their spring legislative sessions.

In New York, state lawmakers introduced several bills that would ban corporal punishment in public and private K-12 schools after a Times Union investigation found more than 1,600 substantiated cases of school staff members spanking, slapping, choking and dragging students and intimidating them with a belt, among other things, in public schools in recent years. The state’s yeshivas, traditional Jewish schools, have also come under intense scrutiny for physical abuse allegations.

Though it’s unclear how often corporal punishment is used in Colorado schools since the state doesn’t collect that data, lawmakers there are considering legislation that would ban it entirely. A similar effort in 2017 fizzled in the Republican-controlled Senate after it passed the House.

Despite mountains of evidence showing corporal punishment is harmful, the idea of moving away from the discipline practice remains a hard sell for some conservative states and districts.

In fact, the school board in Cassville, Missouri, voted to reintroduce corporal punishment – specifically paddling on the buttocks – this school year at the urging of parents, school officials said, even though the practice had been banned for more than two decades.

And last week, Republican legislators in Oklahoma voted down a ban on corporal punishment for students with disabilities. The proposed bill got more yes than no votes, 45-42, in the House but failed to get a majority. A slightly watered down version passed the chamber earlier this week.

“Several scriptures could be read here. Let me read just one, Proverbs: 29: ‘The rod and reproof give wisdom, but a child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame,’” Republican Rep. Jim Olsen argued during floor debate. “So that would seem to endorse the use of corporal punishment.”

Similar beliefs were on display in Colorado last week as well, before the House overwhelmingly passed a ban, 48-16, sending the legislative proposal to the Senate.

“Pain is a primal motivator. You learn via pain,” Rep. Ken DeGraaf, a Republican who represents Colorado Springs and who voted against the bill, told reporters. “Sometimes it’s best to experience an artificial or synthetic consequence before it’s permanent. There are too many adults in our jail system right now experiencing life-long consequences because they did not experience the synthetic consequences.”

Notably, corporal punishment remains legal because of a 40-year-old Supreme Court decision, Ingraham v. Wright, which held that the practice in public schools is constitutional and, therefore, each state is allowed to make its own rules about physically disciplining students.

Democrats in Congress introduced a bill last year, “Protecting Our Students in Schools Act,” which would prohibit the practice of corporal punishment from any school that receives federal funding, but it wasn’t prioritized by either chamber.