Schools may try to guess other campuses you’re considering and provide a list of their prices. They may not be accurate.

Every year, a new crop of innocents arrive in the marketplace for an undergraduate degree. Very quickly, they get an education in some unwritten rules.

Families often don’t pay the listed rate. Schools offer website calculators that estimate what families may have to pay, but they make no guarantees. Aid seekers can’t get a real price quote until they’ve applied and been accepted.

And if a student is considering a school like Manhattanville College in Purchase, N.Y., something strange could happen when the student both seeks the estimated cost and gets the real one after being accepted: The college will quote the prices from five competitors, even though the student didn’t ask for them. Those quotes may all be higher than Manhattanville’s, too.

These estimates come with a big disclaimer: They may be wrong. As you can imagine, some of these other schools are not thrilled with this state of affairs. So why would an institution that offers instruction in mathematics and economics put out suspect figures?

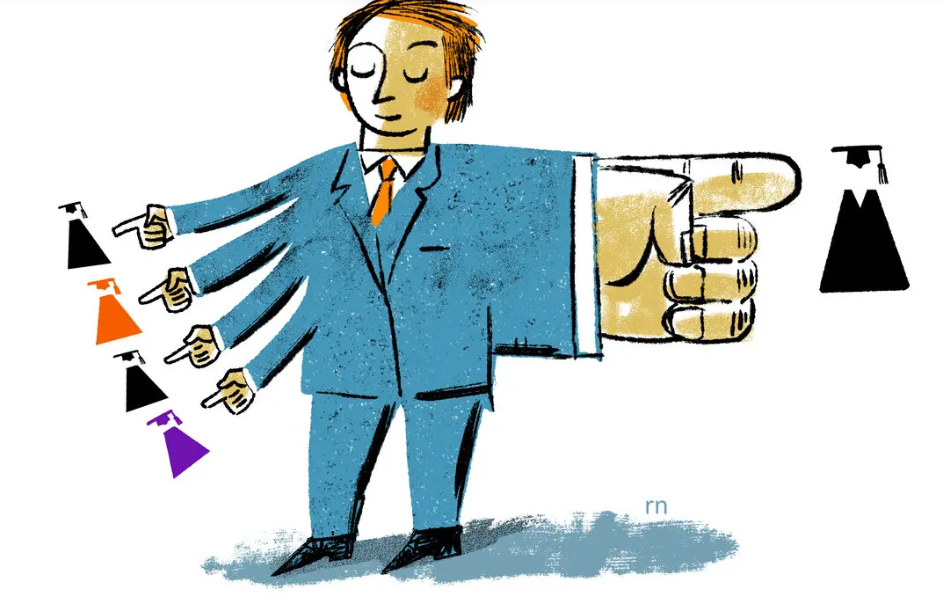

That question — and its elusive answers — underlie a basic issue that comes up each admissions season: College applicants and their families are at a severe information disadvantage, and many of the people who could do something about it are in no big rush to make things less complicated.

Since 2011, the federal government has required all colleges to post something called a net price calculator on their websites. College shoppers enter a bunch of financial information, and out comes an estimate of what the college may ask an admitted student to pay.

Net price calculators are much better than nothing. At their best, they prove that a college’s list price is a kind of fiction for many, or even most, students.

The calculators, however, are often confusing. Detailed studies have called out their shortcomings.

The problems with the calculators are nobody’s fault but also everyone’s. The government doesn’t set strict enough guidelines, addled families enter incorrect numbers, and colleges use subpar calculators or don’t regularly update the tool’s formulas. Moreover, while the calculators predict financial need, based on your earnings and relevant assets, they may not try to estimate so-called merit aid, which is based more on what a high school student has done inside or outside the classroom.

When William E. Staib, a technology and financial services industry veteran with six children including a foster daughter, first surveyed this mess as a parent, he — like other parents I wrote about two weeks ago — figured he could build a better tool. Today, over 250 schools license his net price calculators, and his company, College Raptor, offers rankings and other information on a website for consumers.

Here’s how that comparison works. If it’s comparing a client school with a competitor that also happens to be a client, it pulls estimated prices from that other school’s net price calculator — the one that College Raptor runs.

If the competing school is not a client, College Raptor uses federal data and other proprietary mechanisms. Then, according to its marketing materials, “advanced A.I.” takes over. Clients get a list of comparable schools, and they can choose which ones — the more expensive ones, it seems — to show prospective students. They can reveal those competitor prices on the results page of their net price calculator and on the so-called award letters that they send to admitted students.

Three of Manhattanville’s five comparison schools — Marist and Mercy Colleges in New York and Drew University in New Jersey — declined to comment or did not want to criticize a competitor’s tactics. The other two had some objections.

“These tactics make it more difficult for students and families to make accurately informed decisions,” Drew Aromando, vice president of enrollment management at Rider University in Lawrence Township, N.J., said in an email. “There are too many unique variables in the financial aid process for one college to estimate for a student/family what they can expect to receive in financial aid from another institution.”